HOW “HUMAN” WILL ROBOTS BECOME?

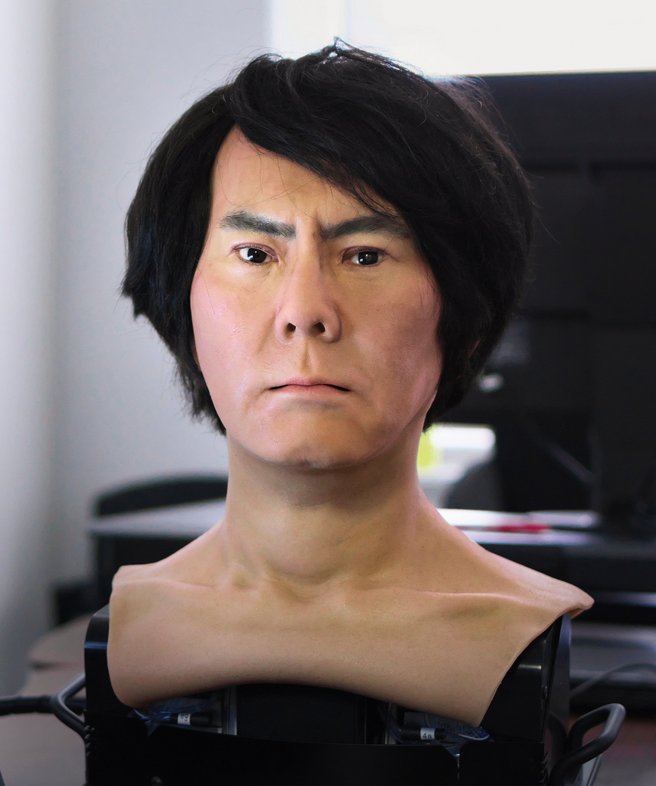

If you happen to end up chatting with Hiroshi Ishiguro via video, you really have to look closely to avoid confusing the robotics rock star with the machine next to him. It blinks like he does, nods the same way and tilts its head to the side in an almost perfect imitation. The machine next to Ishiguro doesn’t just look human, it looks like Ishiguro himself.

Ishiguro, 57 years old, with his thick black hair and intense gaze, runs his finger over the cheek of his doppelgänger made of plastic, circuit boards and metal. “The skin is made of silicone, the hair is real,” Ishiguro says. “His head moves ever so slightly, just like a real person’s.”

Ishiguro christened the robot “Geminoid HI 5.” The fact that it lacks a beating heart is initially only apparent from the fact that it doesn’t have a torso. Its predecessor, “Geminoid HI 4,” which is leaning against a wall behind Ishiguro, does have a body. This robot is also a mechanical twin of the scientist, and Ishiguro uses it as his representative during lectures at Osaka University. Students can ask the “real” professor questions later online. “My students like Geminoid HI 4 better anyway,” Ishiguro says, gesturing to the figure behind him. “His face is gentler, not as stern as mine.”

Ishiguro, who, with his creations, has featured in advertising for Gucci, has experimented with about 30 humanoids: human-like robots. One of his stars is “Erica.” The brunette robot woman even trumps Ishiguro’s Geminoids, which need to be remote-controlled by humans. As Ishiguro explains, Erica can already hold up to ten-minute conversations on her own. “She’s completely autonomous.”

Her chest rises and falls in the process, her camera eyes film the conversation partners. The robot woman surveys faces, detects voices and adjusts her emotions, facial expressions and gestures to each situation. She smiles, nods or asks questions. “Visitors in hotel lobbies enjoy conversing with her,” Ishiguro says. As a receptionist consisting of bytes and metal, she is familiar with more than 150 topics. Some hotel guests couldn’t believe Erica was operating without being remotely controlled, her creator says proudly.

Like many other robotics researchers around the world, Ishiguro is fascinated by the question of how people react to machines that look like them. Or that behave like them— since they express joy, sorrow or fear, i.e. show emotions, which is actually a core human quality. Ishiguro wants to find out how to get people to accept these new social companions. After all, he says, it’s just a question of time before we encounter them in offices, nursing homes, supermarkets and living rooms.

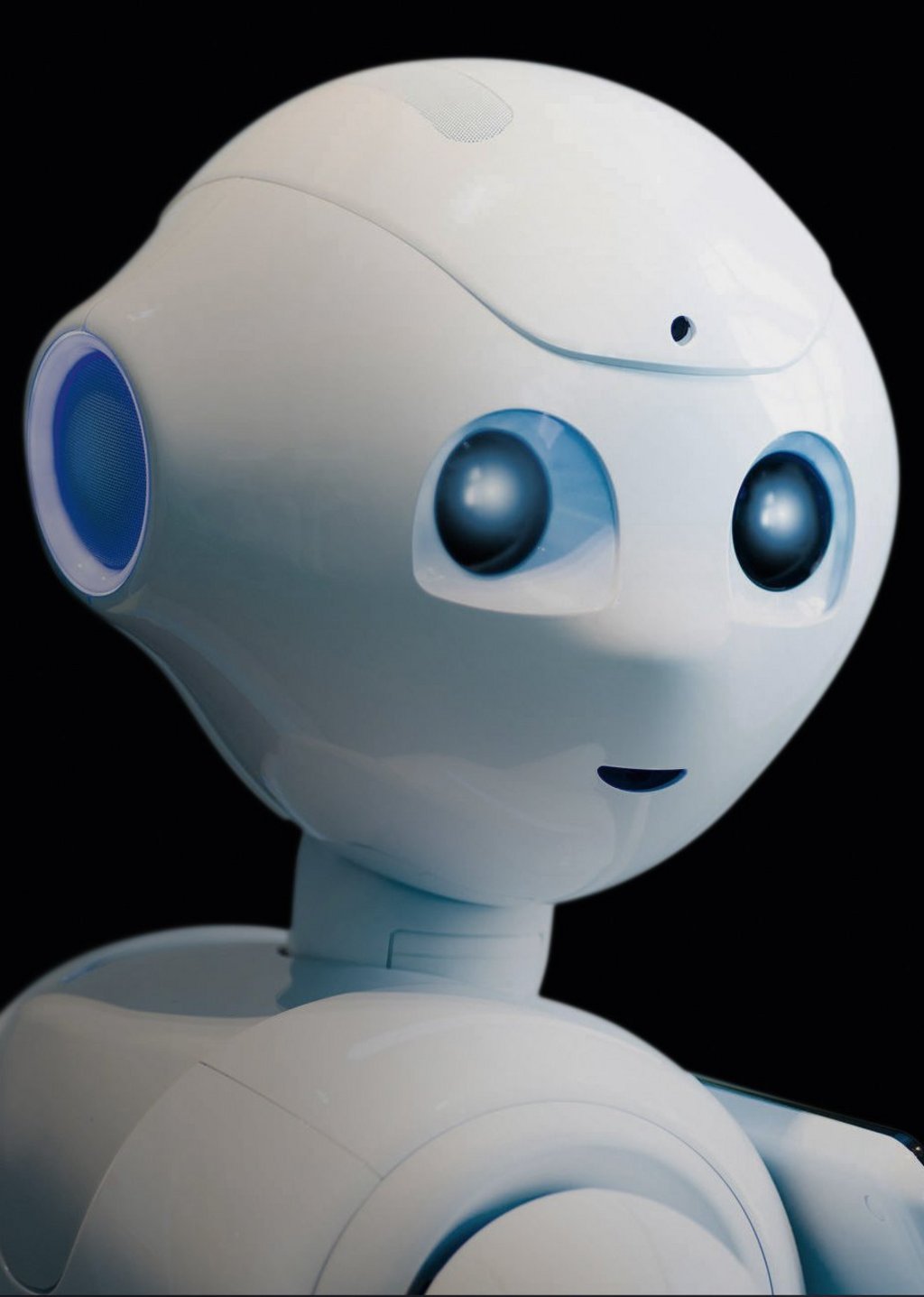

Along with Ishiguro, Ruth Stock-Homburg, 48 years old, is also relatively certain of this future scenario. Stock-Homburg, a professor of marketing and personnel management at TU Darmstadt, estimates that “in four to nine years, social robots will have been integrated into work teams in our office environments.” This also includes robots with human features and forms, which are grouped under the umbrella term humanoids—including Pepper, the world’s first social humanoid robot, who has been rolling through foyers and hospitals worldwide for years. When such robots are particularly human-like in appearance—because their skin, hair and voice are completely modeled on human beings—they are known as androids, as in the case of Erica.

Corona has further accelerated developments in this area. According to Stock-Homburg, the pandemic has radically increased the acceptance of robots. This is reinforced by two studies conducted by TU Darmstadt that investigated the use of robots in customer contact and in teams within companies since the outbreak of COVID-19. The surveys showed that more than two thirds of respondents see clear advantages for service robots, for instance in retail shops, where they could lower the risk of infection. In companies, as well, the majority of respondents want to use interactive robots.

Until recently, Stock-Homburg would have considered this fanciful. After all, these mechanical companions still frequently misunderstand people, for instance when there is a lot of background noise or when people mumble or speak through masks. Nonetheless, she sees unexpected development possibilities for interactive robots due to progress and improvements in hardware and computing power as well as leaps in quantum computing, not to mention in their mechanics as well. She waxes lyrical about a robot trained by one of her co-workers to play table tennis, with a hit accuracy of 95 percent.

The idea of creating an artificial image of ourselves has fascinated humans for a long time. But what happens if we actually encounter mechanical beings that look so much like us? That act and make decisions like we do? What if we develop an affinity for such helpers made of silicone, circuit boards and metal, created to anticipate our every need? Robots which, as soon as we perceive them as “social counterparts,” will also trigger “social caring” in us—whether we like it or not, as Martina Mara, professor of robot psychology at the Linz Institute of Technology at Johannes Kepler University Linz, points out.

“In four to nine years, social robots will have been integrated into work teams in our office environments.”

Stock-Homburg looks into these questions with the childlike Pepper and with the android Elenoide. Wearing a red blazer, the robot looks like a businesswoman. Like Ishiguro’s androids, she was built in the Tokyo-based A-Lab in Japan at a cost of 400,000 euros. Stock-Homburg’s team equipped Elenoide with algorithms and sensors. So, like the Japanese robot Erica by Hiroshi Ishiguro, she can not only talk to people on her own and sense their moods, she can also react with emotions such as joy or surprise.

The pharmaceutical giant Merck has already tested Elenoide in the HR department for personnel development. Employee response was overwhelmingly positive. One of Stock-Homburg’s main findings is that androids are more suitable than humanoids, such as Pepper, for demanding tasks, for instance when an expert opinion on a complex topic is required. With its large, childlike eyes, Pepper is too cute to be taken seriously. Moreover, robots that are clearly recognizable as machines lack credibility. They are more suitable for simple conversations and tasks, such as looking after guests at a reception desk. Acceptance of a friendly and competent Elenoide, on the other hand, is almost as high as that of a human counterpart, Stock-Homburg says.

Will Jackson, the director of the British android builder Engineered Arts, also knows how differently we react to robots that look more like humans. At a robotics panel discussion, he recounted how employees clustered around a powered-down android as if it could converse with them. “They treated it like a person,” Jackson says.

However, when human-like robots are inactive or stare intently, they can also unsettle people. Stock-Homburg admits that Elenoide can be “fairly uncanny.” She’s referring to the “uncanny valley” hypothesis from Japanese robotics researcher Masahiro Mori. This describes how, as the appearance of a robot becomes more human, acceptance of it increases up to a very high level, but then reaches a certain point and descends sharply, becoming strongly negative. The more human-like the robot, the more uncanny it seems. It isn’t until a robot almost perfectly replicates a human that it again triggers a rise in pleasant emotions.

Hiroshi Ishiguro is fairly certain that his creations have long since left this bleak valley. However this doesn’t apply to his “Telenoid,” which he picks up and puts on his lap. It doesn’t have any gender markers, is white and about the size of a toddler. As Ishiguro explains, with its stubby arms, silicone body and bald head, it’s the perfect neutral projection surface for dementia patients to help them remember. They needed this more abstract shape. The Telenoid is currently being tested in nursing homes—even as the web has reacted with disgust. Under YouTube videos, user comments about the robot describe it as a “disgusting baby” or a “deformed fetus.” One user even wrote, “Burn it!” Unlike the cute Pepper and the Ericas and Elenoides of the world, robots like Telenoid fail the acceptance test. Robots shouldn’t be creepy or freakish.

At the same time, some experts find they also shouldn’t be too human-like, an opinion shared by Alan Winfield, a professor for robot ethics at the University of the West of England, who deals with the ethical questions surrounding androids. “As soon as robots look like humans,” he says, “we’re vulnerable. We cannot help but react emotionally to them.” We humans tend to anthropomorphize in such cases, attributing human characteristics to objects. Especially when they resemble us or offer strong “social stimuli,” such as emotions of sadness or fear.

Barbara Müller, a 39-year-old assistant professor at the Behavioural Science Institute of Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, has found that such concerns are in fact justified. In a study conducted in cooperation with the LMU University in Munich, she investigated the extent to which subjects were willing to sacrifice humans instead of robots. To make the decision more difficult, the study designers attributed human emotions and decision-making capabilities to the robots.

The result: the more human-like the robots, the less willing the subjects were to destroy it. That in itself was “absurd” on its face, as Müller describes it; after all, a person has to know that robots don’t feel as we do. What was “shocking but not surprising” to her, however, was that the empathy of some subjects went so far that they would have preferred to sacrifice a group of people rather than the poor robots. Müller’s team has been able to replicate the results in further experiments.

“Anyone familiar with human-robot interaction knows that we react with particular empathy when machines simulate emotions.”

For Markus Appel, a communications psychologist at the University of Würzburg, this is “a game changer. We are then reacting with the schemata we also use with other humans.” As described in robot-human research, this means that humanoid machines are “socially contagious.” When they act happy, we feel better; when they appear to be “suffering,” we suffer as well. This is underscored by experiments conducted by Kate Darling.

Darling had subjects play with a cute squeaking dinosaur robot. Afterwards, most refused to behead the robot on Darling’s instructions. One subject even clutched her dinosaur and removed the battery “so it wouldn’t suffer.” Test subjects from the University of Duisburg-Essen had a similar experience. They couldn’t bring themselves to unplug “Nao,” the little predecessor of the robot Pepper, when it called out, “Please don’t turn me off! I’m afraid of the dark.”

Studies show that lonely people are especially likely to strongly anthropomorphize. This leaves them vulnerable to exploitation, warns Joana Bryson, professor for ethics and technology at the Hertie School Berlin. “The sense of empathy is that much stronger, the more similar someone is to us,” she says. Manufacturers take advantage of this in their marketing. The deceptive thing about it is that machines are in fact not at all like us. As Bryson notes, “Rats are more like us than robots.” Pretending that machines can feel emotions like humans is therefore dangerous and manipulative. This is why Bryson is urging that manufacturers be transparent about how and what machines are programmed to do. “It must be clear what a machine can and more importantly cannot do,” Bryson says. For us to accept robots yet not become slaves to them, researchers are also advocating that social robots be developed in such a way that the focus is less on “affective trust” and more on “cognitive trust.” Acceptance by way of enlightenment instead of emotions.

Stock-Homburg shares these concerns. She, too, has seen how people trusted Elenoide so much that they willingly shared data with her—even if smartphones today vacuum up much more data than robots currently can. Still, she feels that endowing machines with emotions is indispensable. Firstly, it facilitates interaction with them, and, secondly, it increases acceptance and satisfaction. Yet it remains essential “to think about responsible digitization as part of the initial design phase.”

And as she puts it, robotics is something like a butter knife: “You can use it to spread butter on a piece of bread. But you can also use it to stab someone.”