IS THERE ANYONE OUT THERE?

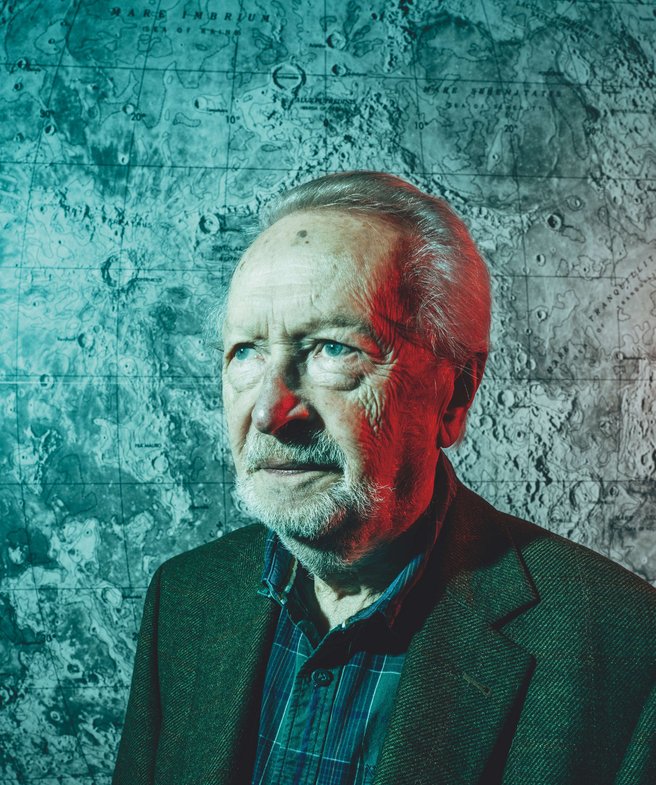

When Dieter B. Herrmann stands up from his desk at night, steps outside the door of his apartment in the Archenhold Observatory in Berlin and looks up at the sky, each time he realizes how little humankind knows about the universe. There are supposedly one hundred sextillion stars, and probably at least as many planets. One hundred sextillion is the number one followed by 23 zeros. “We’ve only discovered 4,281 planets so far,” Herrmann says. The majority of which were detected only with indirect measurements. “We’ve only actually seen three or four outside our solar system.”

Herrmann was twelve when he opened his first book about space in the school library. The year was 1951. Nobody knew if a person would ever make it to the moon. Quite a few believed in Martians, which Herrmann thought was science fiction, and science fiction was never his thing. “I always had the feeling it was a crackpot idea.” Today, he’s not so sure anymore.

“It would be paradoxical to think that we’re the great exception and that intelligent life can only be found here.”

This late summer day, the 81-year-old is sitting in the library of the observatory in Treptower Park in Berlin and is talking about whether there could be intelligent life out there somewhere. For almost thirty years he directed the research station, from the center of which protrudes the world’s longest movable lens telescope. Today the retired director lives in an apartment at the back of the building complex. The press used to call him “the stars professor” because he was the long-time host of the science program AHA on East German television. The International Astronomical Union named the small body 2000 AC204 Dieterherrmann in his honor. He’s currently at work writing his forty-seventh book and still gives forty to fifty lectures a year: about constellations and astrophysics, about the Big Bang and dark matter, about white dwarfs and red giants. And about the question of whether or not we’re alone in the universe.

“Belief belongs in the church,” he says. “But since you’ve asked: there are hun-dreds of billions of suns in the Milky Way, and there are hundreds of billions of such galaxies. It would be paradoxical to think that we’re the great exception and that intelligent life can only be found here.”

As a scientist, Herrmann knows that only that which has been proven is considered to be true. And as of yet, no proof has been found for extraterrestrial life. According to the Rare Earth hypothesis, it is quite unlikely that complex life has developed outside of Earth. The composition and position of our planet, which is so hospitable to complex lifeforms, is something quite rare in the universe. Yet it is precisely these sorts of considerations that fascinate Herrmann when he considers the question of intelligent life in the universe. This question has captured humanity’s imagination for centuries but remains a question without a satisfactory answer, despite all the research undertaken thus far.

Surveys have found that about half of Germans believe there is intelligent life out in the universe. Back in 1938, when the US radio station CBS broadcast the War of the Worlds radio play, some American listeners thought they were listening to a live report about an actual invasion from Mars. Artists, musicians and Hollywood have been exploring the theme for decades. There are people who fear that the arrival of aliens will wipe out humanity, while others hope for salvation to be brought by alien beings from outer space.

Those who wish to take a more sober approach to the question can speak to scientists such as Herrmann, who has researched planets, stars and galaxies for decades as an astronomer and physicist. Other scientists are looking to determine the conditions under which life can develop and are designing scenarios of what an encounter with alien beings might be like. Such scientists include the astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch and the exosociologist Michael Schetsche, with whom Herr-mann discusses such questions in the Research Network Extraterrestrial Intelligence—and in so doing arrives at astonishing but also frightening prospects.

“Basically, the efforts of the past decades have achieved very little,” Herr-mann says. Because optical telescopes quickly reach the limits of what is physically possible, radio telescopes began searching for signs of life. In the United States, scientists from SETI—the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence—have long been searching for artificial radio waves from space. The researchers’ thesis is that if there is a technically developed civilization, it should also have radio technology. Gigantic research stations have been built at sites such as the Arecibo Observatory on Puerto Rico, which had a reflector dish measuring 305 meters in diameter. For the SETI@Home project, millions of people provided access to their private computers to help evaluate the masses of astronomical data being received. Yet on March 31, 2020, the project was stopped—without any results.

“We don’t even know if the search for radio signals was the correct strategy,” Herrmann says. Perhaps intelligent alien life forms have completely different technologies at their disposal that aren’t even showing up on our technology horizon yet. “It’s like setting up a radio telescope while the other side is trying to get your attention by yodeling from a mountaintop.”

Former SETI Director Jill Tarter once described the dilemma of the search as follows: to claim that there wasn’t any extraterrestrial life based on previous investigations would be like taking a glass of water from the ocean, not finding any fish in it, and then using that to conclude that there were no fish in the ocean.

“Life is incredibly resilient.”

Perhaps completely different approaches are needed. Like the one Dirk Schulze-Makuch is taking. A professor of astrobiology and planetary habitability at Berlin’s Technical University, he’s investigating places where the hostile conditions are closest to those found on Mars: the snow-free, high mountain valleys in Antarctica or the dry Atacama Desert in Chile. There are hardly any plants or animals there, but a multitude of microbes call these places home. Schulze-Makuch is continually amazed at the conditions these microorganisms can defy. “Life,” he says, “is incredibly resilient.”

For Schulze-Makuch, Mars is by no means the only possible habitat for life in our solar system. For instance there’s the Saturn moon of Titan, which is covered by oceans of liquid methane and ethane, with an atmosphere denser than Earth’s. Or the icy moon Enceladus, also a satellite of Saturn, which has huge fountains of water shooting up from its surface like cosmic geysers. For a long time, it was considered impossible for life to develop under such conditions. Yet now that strange crabs, worms, mussels and starfish have been discovered in the deep sea—creatures that get their energy not from sunlight but instead from the hot gases and minerals of the Earth’s crust—some researchers believe that the origins of life are to be found deep in undersea crevi-ces. Schulze-Makuch considers it possible that on Jupiter’s icy moon Europa there are ecosystems similar to those found at hydrothermal vents in the deep sea, with lifeforms at a similar stage of development as crabs and tube worms. Of course, tube worms cannot build spaceships—but the possibility that there are relatively highly developed organisms in our solar system, practically at our doorstep, illustrates how megalomaniacal it is to believe that Earth is the sole cosmic exception.

A weakness of astrobiology, Schulze-Makuch admits, is that it always starts from the Earth, from life as we currently know it. But biology in outer space may also be completely different. Perhaps life has originated somewhere else on the basis of silicon; maybe methanol works as primordial soup instead of water; what if, according to the idea of a colleague of Schulze-Makuch, genetic information could be passed on by magnets instead of DNA? But perhaps whatever’s going on out there is also “completely out of the box,” as Schulze-Makuch says. So inconceivable that it would be paradoxical to have any idea of it at all.

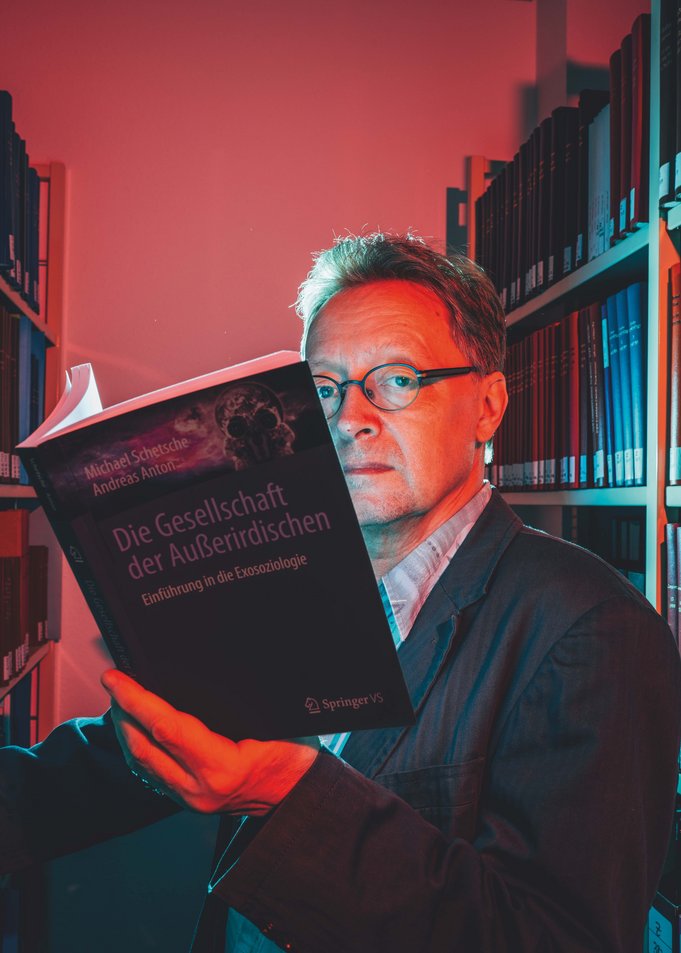

Michael Schetsche calls this inconceivability the “maximum foreignness.” Schetsche, a sociology professor in Freiburg, together with his colleague Andreas Anton founded a new discipline: exosociology. The scientists are investigating what would happen in our society if we really came into contact with such an alien—and have worked out three scenarios: one that is harmless, and two with more serious consequences.

In the first scenario, humanity receives a signal. It’s a harmless mind game. The signals probably came from so far away that whoever sent them could never visit us, and probably vanished long ago. “It would be a sensational discovery,” Schetsche says. “It would change our view of the world because we would finally have proof that we aren’t alone—but it wouldn’t really give us any cause for worry.”

In the second scenario, we find an artifact of an extraterrestrial expedition somewhere in our solar system: a probe or a station, but perhaps even just its trash. From that moment onward, we would know that there is a technically advanced civilization that has mastered interstellar spaceflight—and that they were here at some point. “This would lead to a general sense of insecurity,” Schetsche explains. “We would have to ask ourselves: Who are they? What do they want? And will they return?” Such a find would also be risky because it would contain valuable technical information and a race would break out among nations and multinational corporations as to who should be allowed to recover the artifact. Schetsche says that under no circumstances should such a find be brought back to Earth. “Experimenting with the propulsion of a probe for interstellar space travel could quickly destroy an entire continent.”

“It would change our view of the world because we would finally have proof that we aren’t alone.”

Yet the greatest levels of shock are found in the third scenario: an actual encounter. If a space vehicle controlled by an extraterrestrial intelligence enters our solar system, it could cause mass panic, stock market crashes and religious upheavals. The fears wouldn’t even be that irrational. You just have to look at the history of asymmetrical cultural contacts on Earth, Schetsche says: “When one civilization visits the territory of another, things usually turn out badly for those being discovered.”

Which is why he’s therefore strictly against turning the tables and sending targeted radio signals into space ourselves, as some members of the SETI community do in the METI—Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence—program. Alien civilizations could have a completely different relationship to living and dying, Schetsche warns. He isn’t thinking about Martians here, or any tentacled creatures—what’s much more likely is that we would end up dealing with “post--biological secondary civilizations”: with machines that were once built by biological beings, but who long ago left behind their creators and their mortality—which is how they can overcome the enormous, interstellar distances.

Schetsche believes that when it really does come to contact, we will be surprised at how alien the aliens are. “It could be artificial intelligence at the cellular level, a kind of biocomputer. And perhaps it won’t be so easy for us to distinguish: Is civilization primary, secondary—or even tertiary?”

Tertiary civilizations? Artificial intelligence created by artificial intelligence? Immortal bio-computers traveling through space? It all sounds just a bit like “crackpot ideas,” as the twelve-year-old Herrmann would have claimed. However, towards the end of our conversation in the observatory, Herrmann also said that over the past seventy years, science-fiction authors were often much closer to the truth than scientists. “And the history of science shows that the world is much more diverse than we ever could have dreamed.”