North of Basel, Switzerland locomotive driver Markus Palm has to bring his train to a stop. The locomotive—painted red, 19 meters long, weighing 84 tons and with 7,600 horsepower—has come to a halt on this rainy Thursday afternoon because the signal next to the tracks close to the German-Swiss border is showing red. The locomotive of the RheinCargo freight company is pulling twenty tank cars holding mineral oil. Tonight, they must first reach a large corporation’s tank farm and then go to a chemical company, where their contents are urgently required.

Yet Palm is just sitting here, and it’s not the first time. “I know this spot,” Palm says. “You often have to wait for faster trains, like a high-speed Intercity Express, to pass by. I’m not going to call up the dispatcher and ask what’s going on or when I can move on.” He just waits. After another ten minutes have passed, though, he does begin to wonder, taps the button next to the train radio display to reach the local signal tower, and grabs the black telephone receiver. And in fact, Palm has to let a passenger train pass before he can get out of the station area and back on his way. Once it’s rushed past on the tracks next to him, he can once again push forward the small, black control lever that he’s had his left hand on, and set his train back into motion.

It was just twenty minutes. However, these twenty minutes are emblematic of where hiccups still remain in the European dream, where improvements need to be made in European rail transport—and why the EU is currently investing billions to make rail an environmentally friendly alternative for even more transport around Europe. According to the German Environmental Protection Agency, freight trains emit seven times less greenhouse gas per ton-kilometer than a truck.

So far, so good. Except that the European rail network has a problem: although it is quite extensive, it is too underdeveloped in many places to handle all the freight and passenger trains. Every day this leads to stress and delays and prevents rail companies from fully exploiting this great potential. Yet it’s urgently needed. The EU wants to transfer heavy freight traffic from the roads to the rails to help meet numerous climate goals, doubling rail freight traffic by 2050 compared to the volume in 2015. Today, the amount of freight transported by rail in Europe is around 400 billion ton-kilometers, about 20 percent of the total. Across Europe, more trains need to be on the rail network, the trains need to be longer, and the rail infrastructure must be expanded. And the various different standards need to be brought into harmony.

To accomplish this, the EU has developed the idea of a Trans-European transport network, or TEN-T, which includes high-speed and conventional rail. To this end, it is defining the infrastructure needed in Europe to optimally connect the continent for transport and trade. At the same time, it is setting up an incentive program for EU funding, the Connecting Europe Facility. If everything works out as Brussels has envisaged, the year 2050 could bring, for rail, a realization of the European dream: no borders, no barriers, one continent.

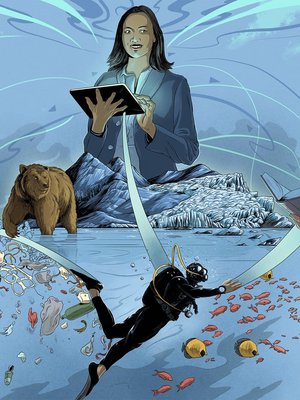

Preparing for departure Before a freight train can depart, locomotive drivers like Markus Palm must check everything again. Walking through the track bed is part of their daily work. If everything’s fine, Palm pushes the lever forward, and away they go.

Rail is best

Locomotive driver Palm shows how important this cross-border traffic is. On this late summer’s day, he’s driving his train along one of the main arteries for rail freight traffic. The Rhein Valley railroad between Basel and Karlsruhe is part of the Rhine–Alps Corridor. It leads from the Dutch and Belgian port cities of Rotterdam, Antwerp and Bruges, through the industrialized belt along the Rhine, via Basel through Switzerland, and down to Genoa on the Italian Mediterranean. The goods arriving via ship at the big ports in Europe’s west and south are then transferred to the railways and distributed throughout the continent.

Rail is the best choice, particularly for bulk goods such as timber, construction materials, ballast, chemicals and fuel. Of the some 5,000 freight trains that travel on the German rail network every day, around half of them cross at least one national border—all the while reducing greenhouse gas emissions compared to road haulage, for example. A freight train can replace up to 52 trucks—and thereby reduce the amount of carbon dioxide accordingly. The EU has defined eleven freight corridors, or routes, that are particularly important for transporting goods across Europe—yet almost all of them suffer from gaps that need to be closed in order to build a rail network upon which European companies can safely and securely load and ship their products.

To best make this possible, it’s essential to verify and inspect the components and also the infrastructure. One person who knows a lot about this is Gregor Supp from TÜV SÜD. “In our Rail Division, we certify individual components such as rails, ties and even rail-fastening systems,” Supp explains. “Furthermore, we also do inspections as a notified or designated authority.” For this, there are international standards that must be complied with for the majority of applications. Supp and his eleven-member team carefully check whether the components being put on the rails comply with these standards. In second and third steps, they also scrutinize the theoretical specifications. For Supp, though, what’s important is how this dovetails with things in practice: “We’re naturally out on location a lot to validate everything as it’s actually being used,” Supp says. “On the track bed, several of our experts are usually on the road for a few days and take a close look at everything.” It starts with drainage conditions, includes the state of the gravel bed and ends with checking whether all the components have the required certifications. “It’s important that we work accurately because the safety of the infrastructure depends on it,” Supp says. Overall, there are more than 400 multidisciplinary experts at TÜV SÜD who verify, certify and inspect rail applications in every conceivable facet, right down to the safety systems and along every part of the life cycle.

Eliminating bottlenecks

It’s this sort of work that benefits people like Markus Palm. Out the right-side window of his locomotive, we’ve been passing areas leveled by bulldozers, with occasional construction vehicles and mountains of gravel here and there. The route Palm is taking is one of those bottlenecks where cross-border trips often get held up and the delays can sometimes stretch for hours. “But something is happening here, as you can clearly see of late,” he says. South of the city of Müllheim, Germany, two new sets of tracks are being built next to the existing line. By 2035, the route between Basel and Karlsruhe will have a third and fourth track along its entire length, some of which will be able to handle high-speed traffic of up to 250 kilometers per hour. The slow freight trains and faster passenger trains will then be able to use different tracks. Freight customers will receive their deliveries more reliably and travelers will be able to reach their destinations more quickly. The EU is contributing up to 311 million euros to the TEN-T project for this section of the expansion.

Uniform standards

The purposeful expansion of railway infrastructure in Europe isn’t the only thing the EU is aiming for with its initiatives. The network will also be harmonized to simplify cross-border journeys. This is particularly vital for freight traffic, due to its exceptional international importance. Until now, the railway networks of individual member states have been strongly nationally oriented, for instance in terms of gauge. In Spain and Portugal, the distance between the rails is 1.668 meters, making it considerably wider than the standard gauge of 1.435 meters used in the rest of Europe. Border-crossing trains must be “re-gauged,” meaning transferred to train chassis with the appropriate gauge. There are also differences in the electrification systems; the voltage in the overhead lines that supply electric locomotives with power differ from country to country. Germany, for instance, uses 15 kilovolts, while in France it’s 25. Train safety systems across the countries of Europe, which are of course essential for the security of train operations, are also largely incompatible. The safety systems can determine whether a train has stopped at a stop signal and, if it hasn’t halted, can trigger emergency braking to prevent trains from colliding (as just one example). Germany uses the Indusi, LZB and PZB systems, while France uses Crocodile and the Netherlands ATB.

To deal with these different systems, rolling stock manufacturers and railroad equipment manufacturers have found sometimes complicated solutions. For passenger and freight trains, it may be that the locomotive gets swapped out at the border. There is also the possibility of equipping locomotives and multiple-unit railcars with different “country packages,” although this, too, is complicated over the long run.

To better network these system bit by bit, the EU has introduced what is known as the Technical Specifications for Interoperability, or TSI. Among other things this includes specifications for infrastructure, rolling stock, rail noise and accessibility. Yet it cannot eliminate all the differences. For instance, the TSI for energy describes four different electrical systems that exist side by side. Nonetheless, the regulations are intended to limit further national distinctions while still creating as much standardization as possible.

Safety technology is crucial

Palm is now driving his train at a leisurely pace, with no major traffic jams. During the journey along the section currently being expanded, every now and then he points out yellow boxes the size of shoe cartons, located in the middle of the tracks every few meters. “Those are Euro balises, part of the ETCS system that will come online when the upgrades to the line have been completed,” he says. ETCS, the acronym for European Train Control System, is the biggest harmonization project on the European network. The different national train control and safety systems are going to be replaced by a European standard, with Switzerland also involved. The new system could allow up to 30 percent more capacity without one new meter of tracks being built—at least that’s what the rail industry and politicians hope. This is to be achieved through better communication between the tracks and the vehicle. In conventional systems, the lines are divided into blocks upon which only one train at a time is allowed. While the block is occupied, no other train is allowed to enter it, even though there would be enough space for a second train. With ETCS transponders, the train is constantly transmitting its position and the trains will thus be able to follow each other at closer intervals than before. The EU hopes to implement this by 2050 as well.

To date, only around 20 percent of the 42,000 rail vehicles in Europe are equipped with this new standard. But by 2030, half of the vehicles on the important lines will have ETCS onboard units. One sticking point is the financing, which can cost a few hundred thousand euros. ETCS equipment is already mandatory for new railcars running on border-crossing lines, and the EU plans to create incentives for outfitting older vehicles.

Markus Palm’s locomotive isn’t yet equipped with ETCS, but will be. He’s made relatively good progress today and will arrive in Frankfurt at around half past midnight. At that point, his shift ends. The next day, he’ll board another freight train and drive it across the continent that is trying to become ever better interconnected.