ARTIFICIAL CREATIVITY

In the year 1950, the deputy director of the computing laboratory at the University of Manchester published an article that read like science fiction. Would it ever be possible, a certain Alan Turing asked, for a machine to think, in the human sense of the word? Turing suggested a test for this, which he called an imitation game, in which a person converses by text with a machine and with another person. If the person cannot tell which of the conversation partners is the machine and which is human, then the machine has passed the test—and has achieved something like artificial intelligence.

Scientists are still arguing about whether a machine has passed what has come to be known as the Turing test. And yet nowadays we’re surrounded by so-called artificial intelligence (AI) in many areas. Translation software, stock price forecasts, product recommendations, language and facial recognition: they all work with artificial intelligence. Algorithms analyze enormous amounts of data, recognize patterns and use them to solve problems. Over time the computers understand when they make mistakes and when they’re correct. Thus they are also learning.

“We must take a pragmatic approach to the topic of AI and art.”

Just as machines became established in the factory production halls during the nineteenth century, computers are now ubiquitous in offices. There’s just one arena in which they have been virtually absent to date: creativity remains a problem for even the cleverest of algorithms. Smart computers have been able to calculate, recognize patterns and perform many tasks better than humans for years, however they continue to show signs of weakness when it comes to creating completely new things or thinking independently.

Meanwhile, imagining a machine as an artist doesn’t sound nearly as absurd as it may have in the past. “We must take a pragmatic approach to the topic of AI and art,” says Reinhard Karger. Karger studied theoretical linguistics and philosophy and has been working in the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence for the past 27 years. He argues that AI currently provides artists with fantastic tools but is really nothing more than a paintbrush. AI can already work combinatorially in an artistic fashion; it can combine familiar things in new ways and thereby imitate the style of famous authors or composers, for example. Yet it reaches its limits when it comes to actual creation. “It lacks the access to being human,” Karger says.

But is that why an algorithm isn’t creative? At the end of 2018, the auction house Christie’s sold an artwork that had been “painted” with assistance from AI—for 432,500 US dollars. Computers now independently write sporting news and press releases. Singers use AI to help compose new sounds and complete songs. This all begs the question: how creative can a computer be?

Ai-Da is standing in front of a mint-green wall, ready for a difficult task. The artist, with black hair, dark eyes and wearing a white smock splattered with paint, is going to try to paint consciousness. But what does consciousness look like? Is it blue? Red? Abstract? Detailed? This is actually much more complex for Ai-Da, since she doesn’t even possess the consciousness that she is supposed to express.

Ai-Da is a robot, created by gallerist Aidan Meller and equipped with an algorithm developed by researchers at the Universities of Oxford and Leeds. Her skin is made of silicone and her eyes are cameras. With the cameras she records what happens in front of her and that’s also exactly what she puts down on the canvas. Her algorithm helps her to abstract the impressions. Meller doesn’t wish to reveal exactly how this works, just this much: the images from the camera eyes pass through several layers that are similar to filters. The algorithm ensures that each decision process remains unique. This way, Ai-Da never takes the same “thought” pathway. Each of her artworks is unique.

The robot’s paintings have brought in one million euros so far. But is it art and is it actually creative? Or is it just replication of the known world as the algorithm dictates? “Humans create something new from what they see and call it art,” Meller explains. “Ai-Da is doing the exact same thing.” Of course, Ai-Da doesn’t have consciousness, nor feelings, but she’s still creative despite this, “because she creates something new from the known.”

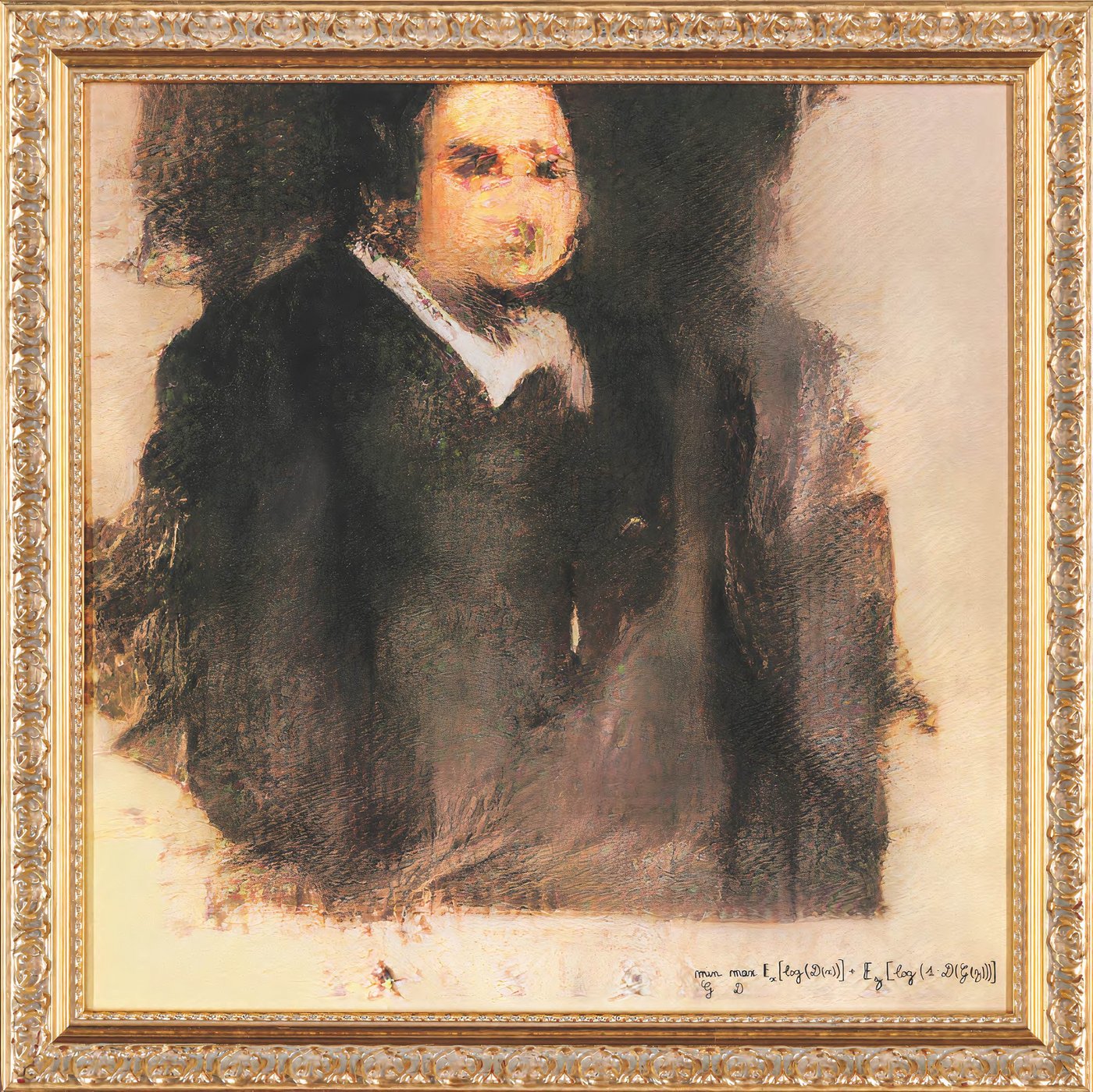

Around four hundred kilometers away, the three founders of Obvious Arts reveal a bit more about the technology of their art project, one that has already earned them quite a bit of money. The painting Portrait of Edmond de Belamy shows a man, dressed in black, slightly blurred—and was auctioned off for almost half a million US dollars. The algorithm that created the painting was written just for this single painting, as Gauthier Vernier, one of the group’s three founders, explains.

The artists had two algorithms that played a sort of game with each other. Algorithm 1 was fed with many old portraits in order to define what a classic painted portrait looked like. Algorithm 2 was not told what was going on. Instead, it was instructed to paint a painting that Algorithm 1 considered “real.” Then the game began. The first painting Algorithm 2 created had nothing to do with a classic portrait and was rejected. As was the second one. But the deception algorithm got better and better with each try. “You have to imagine a teacher who is familiar with all the Picassos in the world, and a student who’s never seen a Picasso and must paint a deceptively real one,” Vernier explains. “The student then practices until the teacher is convinced.” As soon as Algorithm 2 was able to deceive the test algorithm in 51 percent of all attempts, they allowed it to create a painting from what it had “learned,” based on the old patterns that define a portrait but still completely new.

The machine as artist, and a creative one at that? Vernier waves off the question with his hand. He views the algorithm similarly to the way AI expert Karger does, seeing it as a tool. After all, he says, people influenced it, wrote it and fed it with selected data sets. “We do believe that the algorithm can invent something because it makes something new of what’s known, and there’s a random factor that even we cannot influence,” Vernier says. He also says the AI has its own style that a person can recognize, for instance because it places pixels where most people wouldn’t expect to see them in portraits. “But the machine will never be able to completely ‘think outside the box’ like Van Gogh or other artists, creating what many would only then call creativity,” Vernier says.

He still considers the algorithm’s work to be art, as the auction of the painting has already shown. And in any case, art is in the eye of the beholder—whether a human being or a camera’s lens.

Right at the start of her video to the song Breaks Free, Taryn Southern looks directly at the camera in a close-up shot and sings, “I wish I could see, beyond what I can see.” The camera jerkily moves closer and closer to her face while Southern’s expression remains calm. Everything looks like it does in dozens of other pop songs before this one, and it all sounds very much like pop as well. It’s just that Southern didn’t arrange the song completely by herself—she had some help from AI. Just like the entire album the song was released on.

Since Southern released her AI album back in 2017, she’s become a sort of ambassador for artificial intelligence in the music business. While producing the album she tested a number of music AIs at once. “Basically, they all work using similar principles,” she explains. “You feed the AI with data, for instance a series of music pieces from the 1970s, and the AI uses them to create new music that follows similar patterns and rules within the genre.” In the next step, Southern is played an initial proposal piece. By adding even more data, she can steer the AI in the desired direction. After that, she can continue to make adjustments, for instance by increasing the beats per minute. Fundamentally, Southern isn’t doing anything differently than when she goes into a production studio, except that she can control everything herself with the help of AI. She doesn’t need other musicians or a producer sitting next to her.

Southern explains that this can be an enormous help, particularly in the beginning of a musician’s career, since many cannot afford to hire an expensive producer. Depending on the program, the AI spits out an audio file of the finished song or several smaller snippets of the individual instruments. Some programs even output—very traditionally—actual notes and sheet music. “AI won’t be turning the music industry completely upside down, but for many musicians it will absolutely be a new practical tool for their composing process,” Southern finds.

Of course, AI can be used for much more than just producing a new music album. In Berlin, Oleg Stavitsky co-founded the app Endel, which he developed with a small team. It delivers sounds generated in real time that are adapted to the time of day, the weather or even one’s own heartbeat. These sounds, often reminiscent of the soundtrack from a science fiction movie, are designed to help you concentrate, fall asleep or simply just relax. The data for the AI comes from composer and co-founder Dmitry Evgrafov. As soon as a user activates the app, it accesses the composer’s work, incorporates parameters including the time of day, and then generates suitable new sounds.

In spring 2019, the record label Warner signed a contract with Endel and published twenty albums created by the AI on music streaming services including Apple Music and Spotify. The developers have set even more ambitious goals for themselves this year: Endel should soon be able to generate the perfect background music for a car drive.

Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3: this unwieldy name caused an uproar in the world of professional copywriters in June 2020. Behind it is a copywriting machine, driven by artificial intelligence and developed by the San Francisco-based software company Open AI. The New York Times described it as “more than a little terrifying.” The British Guardian newspaper commissioned an entire article about AI and its potential dangers—written by the AI itself. Even the program’s developers warned about the technology’s risks and spillover effects at the same time as they went public with the program.

To show what GPT-3 can do, its developers uploaded just half a press release for publication on its website. Anyone who wanted to read the rest of it could have it generated by GPT-3. There were hardly any noticeable differences to the first, human-written half.

Yet the technology behind this text machine is basically nothing new. The program is fed existing texts and learns the probabilities of words or sentences following one another. Still, the sheer mass of data fed into the algorithm, not to mention its finesse and fine-tuning, are better than ever. Even a novel written by AI could be conceivable in the future.

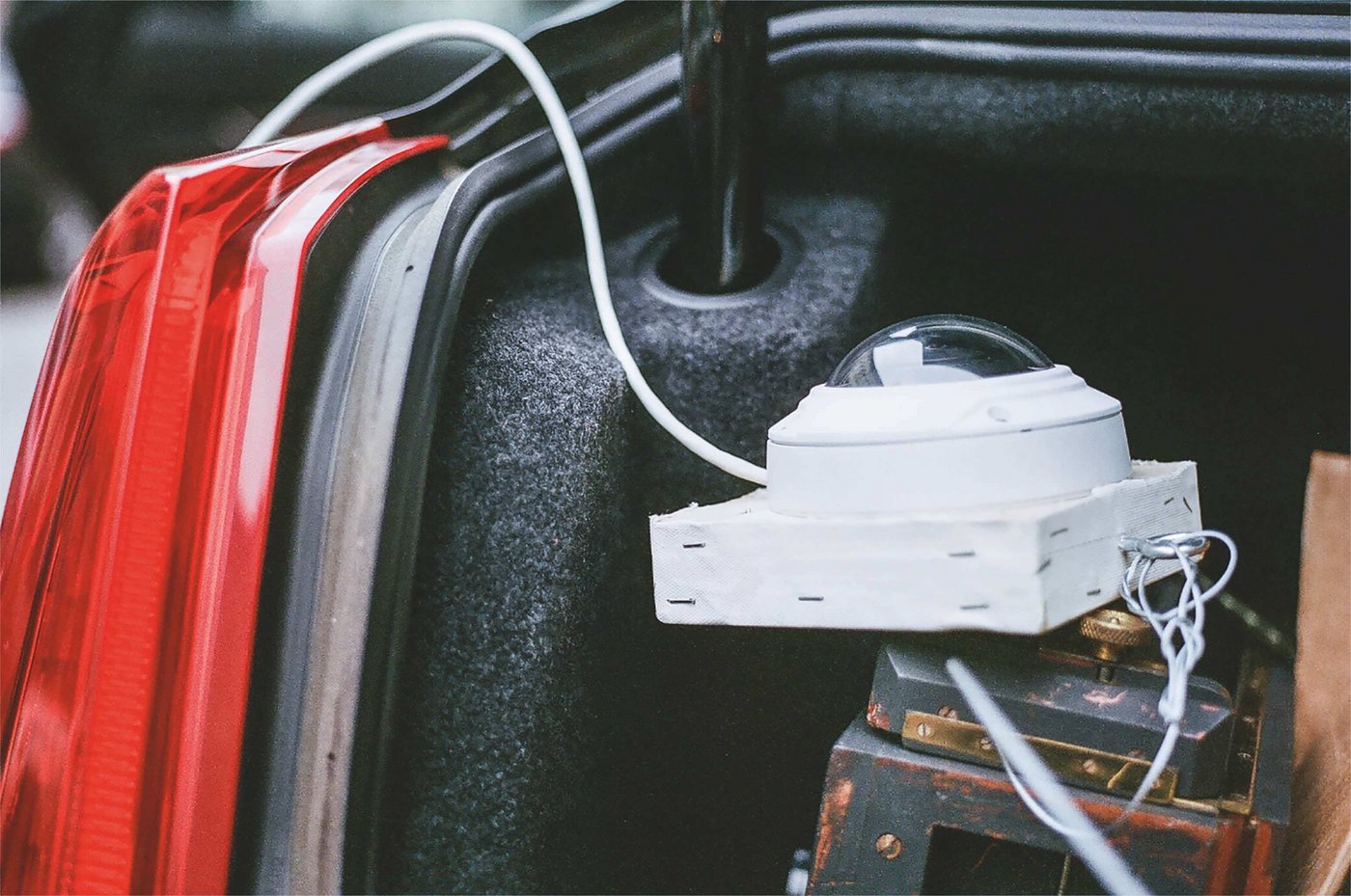

“I had wanted to let a car write a novel for quite some time.”

As the foundation for his idea, he eventually took the novel On the Road by American Beat writer Jack Kerouac. Like the original it was emulating, Goodwin’s work would be written on a road trip from New York City to New Orleans. Except that it wouldn’t be Goodwin, pen in hand, writing down his experiences along the way, but a software made up of lines of code. In 2017, he converted a car according to his ideas: a camera mounted on the trunk to film the passing scenery, a microphone in the interior to record conversations, a GPS sensor to track the location. In other words, huge amounts of data for the algorithm to fashion a novel.

The result? It was “choppy” and full of typographical errors, as Goodwin himself admitted. “It was all an experiment and I published the results accordingly,” he says. While the work of the original begins with the sober statement “I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up,” Goodwin’s car begins much more mysteriously with the sentence “It was nine seventeen in the morning, and the house was heavy.”

The reason for the different performances of GPT-3 and Goodwin’s car: texts such as press releases, sports news or stock market reports follow clear formulas, patterns that an AI can learn. Literature, in contrast, lives precisely from the chaos of creativity. Here, patterns that can be meaningfully reproduced are something that artificial intelligence has been looking for in vain so far.

Without such patterns, however, machines can hardly become “creative” on their own. They lack what humans call consciousness. Whether they will ever develop this is one of the biggest questions of the present day for Reinhard Karger from the AI Research Center. “Nobody has a satisfactory answer to this question,” he says. From a scientific point of view, he says, it cannot be ruled out that machine consciousness could exist at some point. “But considering everything we know today, this is very, very unlikely.”